Wedding Photos on Film : Three Reasons Why Shooting Film at Weddings May be Dangerous

Wedding photos on film. If you’ve paid any attention to the wedding photography industry on social media in the last few years, you’ve probably noticed a lot of buzz not only from couples who want their wedding photos on film, but from photographers who shoot film at weddings. “Artistic”, “dreamy” and “ethereal” are some of the words I’ve read to describe wedding photos on film. What isn’t discussed, however, is just how many drawbacks there are to shooting weddings on film.

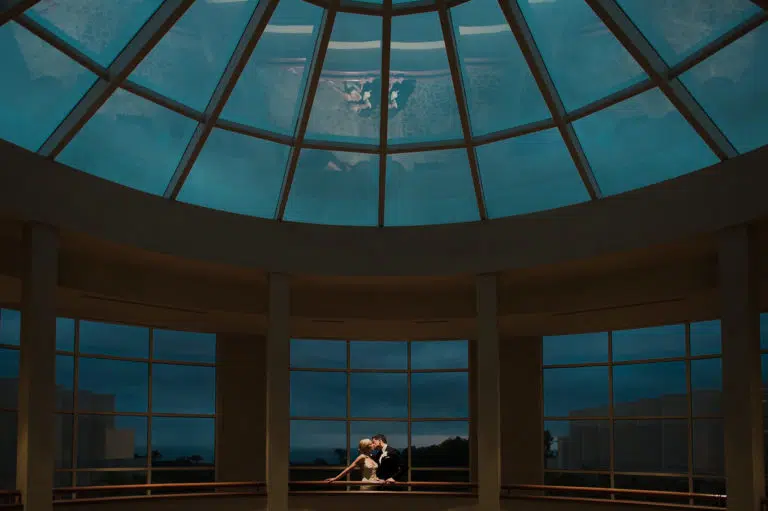

My name is John Schnack and I’m a wedding photographer in San Diego. For the last twenty-one years, I’ve helped over 400 couples curate a premium wedding photography experience. I began my wedding photography career shooting film, then switched to digital, then switched back to analog wedding photography from 2012 to 2014, and then back again to digital. And before that, I was a photographer for a daily newspaper when the only option was to shoot film.

Suffice it to say I’m extremely well versed in shooting and processing film. If you’re a film wedding photographer, or you’re considering shooting weddings on film, I’m here today to talk to you about why shooting film at weddings may be dangerous.

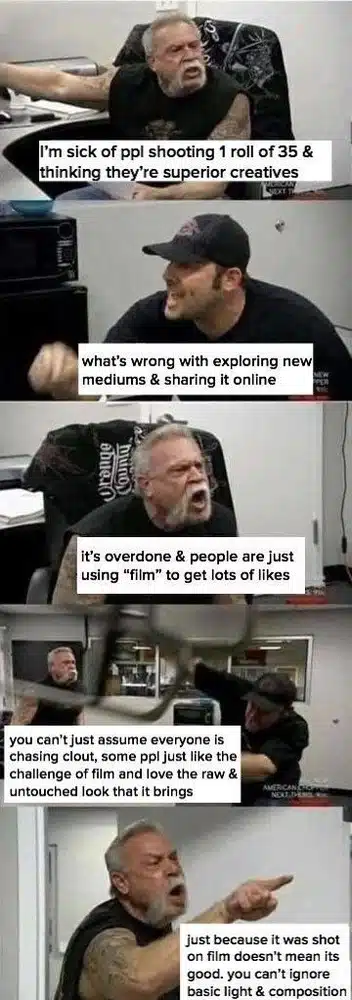

The Medium isn’t the Message

Photography–like music, painting, sculpture, etc.–is an art form. And in photography, there are basic compositional rules that, when followed, create a more artful and impactful photograph for the viewer. Not to say that these rules are steadfast and must be followed at all times–it is art, after all; I’ve seen plenty of impactful photographs that break the rule of thirds, for example.

But what these rules do is establish creative intent. And when coupled with the unique technical aspects of photography–focus and proper exposure–they elevate the photographic artform to more than just pointing the camera and depressing the shutter release.

“…the medium–film–has become the message, and composition and technical quality be damned.”

And yet so much of what is popular amongst those who shoot wedding photos on film, and those who love film photography, seems to take neither basic composition nor technical quality into consideration: Grossly underexposed images are considered “moody”, and horribly overexposed photos are considered “light and airy”. Photos of beautiful couples which both miss peak action and are out of focus are oohed and aahed over. And praise is heaped upon photos of a bride and groom in an exotic location–all while the photographer failed to level the horizon.

I would venture to guess that if any of these examples had been captured digitally, the feedback would probably be more critical, and rightly so. So the problem, as I see it, is that there’s a level of forgiveness–on the part of the photographer and the viewer–with wedding photos on film. In other words, the medium–film–has become the message, and composition and technical quality be damned.

But is this the way it should be? Should a crappy wedding photo on film be considered better just because it was captured in analog?

With wedding photos, or any photos for that matter, the message should be the emotional response the composition elicits, independent of the medium. In other words, it shouldn’t matter whether the image was captured digitally, on film, or on tintype–a great photo is a great photo.

Wedding Photos on Film = Increased Costs

Let’s take a look at costs for unexposed film.

| Film Type | Quantity (in rolls) | Price/Roll | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kodak Portra 120 (16 exp) | 15 | $13.59 | $203.85 |

| Kodak Portra 35mm (36 exp) | 15 | $14.99 | $149.90 |

| Ilford HP5 Plus 120 (16 exp) | 5 | $8.50 | $42.50 |

| Ilford HP5 Plus 35mm (36 exp) | 5 | $8.95 | $44.75 |

| Kodak P3200 Max 35mm (36 exp) | 5 | $13.90 | $69.50 |

| TOTAL*: $510.50 |

Now let’s take a look at the costs to process and scan all this film.

| Film Type | Processing (per roll) | Scanning** (per roll) | Quantity | Total* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kodak Portra 120 (16 exp) | $9.50 | $15 | 15 | $367.50 |

| Kodak Portra 35mm (36 exp) | $9.50 | $15 | 15 | $367.50 |

| Ilford HP5 Plus 120 (16 exp) | $9.50 | $15 | 5 | $122.50 |

| Ilford HP5 Plus 35mm (36 exp) | $9.50 | $15 | 5 | $122.50 |

| Kodak P3200 Max 35mm (36 exp) | $9.50 | $15 | 5 | $122.50 |

| TOTAL*: $772.50 | ||||

| GRAND TOTAL: $1283 |

That’s nearly $1300 in costs of good sold (COGS), before you even figure in what you’re paying yourself for the actual services you’re delivering to your clients, from prep and the engagement shoot to shooting and editing all the photos.

Counterargument: Less Time Editing

I’m well aware of the counterargument: Shooting wedding photos on film results in far less time spent on editing and post production. Since shooting weddings on film requires more deliberation and is slower, ostensibly the photographer would be shooting fewer images. And, if the images are exposed properly and scanned by a capable technician, less time would be spent on post production. Maybe a little culling and fine tuning, but that’s it.

This is a totally valid point. When I was shooting film at weddings, I shot far fewer frames compared to what I now shoot digitally. But I could make the counter-counterargument that a super-fast computer, being decisive and quick during culling, and quality film-emulation presets results in me spending around the same amount of time (okay, maybe a little more) on post-production. But that’s $1300 dollars I didn’t spend on film, processing and scanning.

Or, I could outsource the entire wedding to a freelance editor and spend far less than a film photographer would spend on materials.

Risk of Missing Unpredictable Moments

As we all know, weddings are full of very predictable things that happen slowly: details of the bride’s dress, the bride putting on her dress, the first kiss, and the first dance to name but a few.

But a wedding is also full of moments that happen really quickly: A couple’s emotion as they see each other during the first look, a sly look between a bride and groom during the ceremony, a big lift and turn during the first dance.

“You watch in slow motion as the film falls to the ground and slowly unravels, exposing every spent frame to the light. That’s not only $10 down the drain, but whatever gorgeous images you had on that roll are gone. Forever. And you can’t put a price on that.”

It’s these little, unpredictable moments where shooting wedding photos on film can be a real drawback. Say, for example, you’re shooting 35mm film. You started the ceremony with 36 exposures, but now you’ve shot 20 frames and couple are just about to be pronounced officially married. With only sixteen more frames on the roll, maybe it’s enough for the ring exchange and the kiss–two predictable events that rarely involve surprises. But there’s still one great event to come where lots of amazing moments can happen: The processional.

What do you do? Do you rewind the film that’s in the camera, remove it, and reload the camera? That can take 30-45 seconds, and that’s if you’re quick (trust me, you’re not that quick). Do you shoot to the end of the roll and then grab your other camera–which, by the way, probably doesn’t have an appropriate lens for the situation–to shoot the remainder? What if you’re shooting medium format? Is your assistant next to you with a film insert preloaded with 220?

When I was shooting wedding photos on film, this is the situation I dealt with regularly. It was so unnecessarily stressful. When I made the switch back to digital in 2014, I was free once again to shoot without restrictions. No more stressing if the amount of frames I had on the roll would be sufficient to capture those tiny moments that make weddings so wonderful.

Counterargument: Shooting Film is Deliberate and Forces You to Control Situations

Again, valid point. Obviously, the mechanics and associated cost-per-click of shooting film force you to photograph much more deliberately: Compose, focus, meter, press the shutter. When you add on the costs of processing and scanning, there’s the faint sound of a cash register ringing in your ear every time you press the shutter.

But this isn’t a commercial shoot with detailed shot lists and stylists on set to make sure each setup is perfect. Even the most well-planned weddings are chaotic, and even though some parts can be controlled, you need to be able to anticipate those unscripted moments that make everything special. For the reasons I mentioned earlier, this is far easier to do shooting digitally than it is shooting film.

The Lack of Control With Wedding Photos on Film

With digital capture, the amount of technology involved makes image safety and preservation a concern. Hard drives fail and memory cards can get corrupted. But modern digital cameras and the decreased cost of storage have done a lot to mitigate these risks.

Modern digital cameras have two memory card slots, where the card in the second slot can be a real time backup to the images recorded to the first card. External hard drives are cheap, so it’s easy to have multiple backups in your office. Furthermore, cloud storage has become dramatically less expensive, which adds yet another layer of redundancy with little effort and marginal costs.

When you shoot film at weddings, it’s a totally different story, one that starts the moment you change a roll of medium format film.

Let’s say you have an assistant help with your film. Not only do they hold your spare film, but they also take from you the inserts with exposed rolls and hand you a different insert with an unexposed roll of film, so you can reload and continue shooting. Then your assistant needs to take the exposed roll, remove it from the insert and carefully secure the tab so there are no light leaks. Then, your assistant needs to load a new, unexposed roll on the previously exposed insert so they’re ready for the next change.

Now, suppose you or your assistant fumbles an unexposed roll as they’re loading it on the insert. That’s about $10 down the drain, plus it’s one less roll of potential images for your client. Not a deal-breaker, but certainly not something that should happen regularly.

But what if you or your assistant fumbles the exposed roll? You watch in slow motion as the film falls to the ground and slowly unravels, exposing every spent frame to the light. That’s not only $10 down the drain, but whatever gorgeous images you had on that roll are gone. Forever. And you can’t put a price on that.

Let’s say you’re experienced at shooting wedding photos on film and you’ve got an amazing system. You and your assistant are in lock-step, your film insert transfers are buttery smooth, and you’re sure you’ve got feature-worthy images in the can. But you’re still not out of the woods, since the film hasn’t been processed yet.

And this is where all those nightmares about showing up for school without your homework–or worse, without your clothes–come into play. Because the moment you send that film into the lab, you’re relinquishing all control to whomever processes your film. What if there’s a bad batch of chemistry? What if the lab technician mixes the chemistry incorrectly? What if the lab tech crinkles the film while rolling it onto the developing reel?

What about scanning? Has the tech been properly trained on the Noritsu or Frontier scanner? Do they know the color balance at which you like your scans? (I realize a tech can learn your preferences over time, but should is it really worth the wait? What if the tech you like leaves, and then you have to restart the process all over again?)

All of these things spell varying degrees of disaster for your film.

And what do you tell your clients in this situation? “Uh, I’m sorry, the lab tech screwed up and those gorgeous portraits we shot at that spot on the Amalfi Coast are gone.” Do you think the bride who spent six figures on her dream wedding is going to have sympathy for you? Not a chance.

Conclusion

If you’ve taken the time to read any part of this post, you may come away with the notion that I hate film photography. Nothing could be further from the truth. I’ve got a killer Mamiya 645AF kit sitting on a shelf in my office. There is something very pure about shooting with film. If forces you to slow down and to think about what makes a photograph special, rather than the “spray and pray” approach that photographers take so often with digital capture.

But shooting film at weddings is filled with many caveats that can’t be ignored. If you’re thinking about shooting wedding photos on film, you need to ask yourself the following questions:

- Can I charge my clients enough to cover the cost of film, processing, and scanning and still pay myself a fair rate for my services?

- Am I willing to risk missing unscripted wedding moments?

- Am I willing to put processing, scanning–and ultimately, my clients’ finished images–in the control of a third party?

If you feel confident enough in your abilities and systems to answer, “yes” to these questions, then maybe you’re ready to start shooting weddings on film. If not, then you need to reevaluate what’s important to you and your clients before making the leap.

Have thoughts on the subject? Feel free to leave a comment or hit me up on Instagram. I’d love to chat (respectfully, of course)!